A translation of "Переведіть мене через майдан"/"Переведи меня через майдан"

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan?

(the last wish of the old kobzar1)

“Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan2

To the far side, there is a field, I reckon

The bees hum quietly, a little piece of heaven

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

Where there’s laughter, fighting, feasts and food on shelves 3

Where no one hears, neither me nor themselves

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

There cries a woman; in the past we were together 4

Now I’ll walk past, won’t even recognize her

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

With pain, regrets and love, still not forgotten

Here I’ve been brave, and here I have been rotten 5

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan

The drunken clouds, they seem to touch my arm 6

Now it’s my son who sings on the Maidan

Please, would you help me crossing the Maidan 7

Please, help…” The Maidan took him in

and led him by the hand, and he kept walking

As he fell dead, right in the Maidan center

Not knowing there was no field anymore

Excellent thoughts about this poem and its translations are here, in Russian, and here’s another absolutely excellent Russian article where I first found the sad story of the kobzars.

This started like it usually does , by seeing a painfully literal traslation of this poem in English and wishing to play a bit with rhymes (my translation of “February” by Pasternak started similarly). It took me about two hours on my smartphone in bed when I couldn’t sleep, and there are quite a lot of rough edges. I’d like to fix the last part, adding at least some rhymes (something with “before” in the third line?), removing the “Maidan” in the second-to-last, which would allow me to remove the “arm”, and lastly — yes, the SHELVES, my God. Lastly, English pronunciation is hard and I don’t have an intuition for it. This is what happens when you pick up most of your English from IRC.

To understand this poem, two crucial words are “Maidan” and “Kobzar”.

Maidan is a word that’s almost untranslateable from Ukrainian, it’s too deeply ingrained in the Ukrainian culture and mentality. “City square”, “Main square” doesn’t quite cover it, much too narrow and much too meaningless. In every Ukrainian town, at leats traditionally, there’s a Maidan. It’s the heart of the city, it’s where the people gather to sort problems out, where marriages-fights-celebrations happen. Having an important central square is nothing new, but in the Ukrainian mentality it is a much more loaded term.

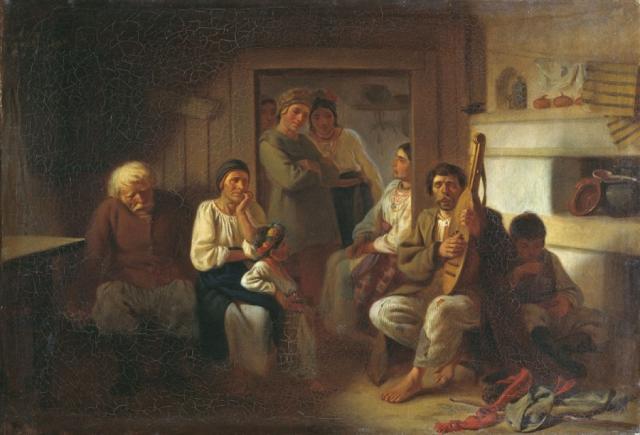

Kobzars were, basically, blind intinerant street musicians, but culturally, again, much more than that. In the 17-19th centuries they were a common sight in Ukrainian towns. Almost exclusively blind, they traveled from town to town, singing folk songs and so called “dumas” (literally translated – “thougths”), which are epics sung in recitative. They usually played kobzas, banduras or lyras, Ukrainian string instruments.

They were the people who created, remembered and sung Ukrainian songs and dumas.

Then, in the 1930, the Soviet government gathered them all together under the pretext of a “congress” and shot them all.

Finding sources about this is nontrivial. Here the fourth paragraph, but I’m not sure how reliable the website is. And here’s the often-quoted fragment from Shostakovich’s Testimony:

I am not a historian. I could tell many tragic tales and cite many examples, but I won’t do that. I will tell about one incident, only one. It’s a horrible story and every time I think of it I feel fear. I don’t even want to remember it.

Since time immemorial, folk singers have wondered along the roads of Ukraine. They’re called “lirniki” and “banduristy” there. They were almost blind men—why that is so is another question that I won’t go into, but briefly, it’s traditional. The point is, they were always blind and defenseless people, but no one ever touched or hurt them. Hurting a blind man—what could be more dishonorable?

And then in the mid thirties the First All-Ukrainian Congress of Lirniki and Banduristy was announced, and all the folk singers had to gather and discuss what to do in the future. ‘Life is better, life is merrier,’ Stalin has said. The blind men believed it. They came to the congress from all over Ukraine, from tiny, forgotten villages. There were several hundred of them at the congress, they say. It was a living museum, the country’s living history. All its songs, all its music and poetry. And

they were almost all shot, almost all of those poor blind men killed.

Why was it done? Why the sadism — killing the blind? Just like that, so that they wouldn’t get underfoot. Mighty deeds were being done there, complete collectivization was under way, they had destroyed kulaks as a class, and here were these blind men, walking around singing songs of dubious content. The songs weren’t approved by the censors. And what kind of censorship can you have with blind men? You can’t hand a blind man a corrected and approved text and you can’t write him an order either.

You have to tell him everything orally. That takes too long. And you can’t file away a piece of paper, and there’s no time anyway. Collectivization. Mechanization. It was easier to shoot them. And so they did.

Back to the poem.

An old kobzar sits near the side of the Maidan. He is old and feels he doesn’t have much time left, and asks to be led to the other side. Before his death, he wishes for peace and quiet. He rememebers — he wasn’t blind his whole life, apparently, — that on the other side there’s a field. The Maidan, while chaotic and hectic, means a lot to him. He rembers everything, his youth, his good and bad deeds (“here I’ve been strong and here I’ve been vile”), his wife(?). Everything revolved around the Maidan, and as a blind person he is very attached to it. He keeps asking to be let to the other side, but no one seems to hear him. At the end, he attempts to do it by himself. He starts walking, but doesn’t get to the other side, and falls dead in the middle of the square. Meanwhile, the town has grown quite a lot in the past few decades, and there’s no field at the other side — his attempt was futile from the beginning.

I have quite a lot of memories connected with this poem, and with the absolutely legendary romance version of the poem translated to Russian. It will always have a very special place in my heart.

I need to play with poetry much more often, it’s about as enjoyable as drawing. I keep forgetting about both.

(Y)

-

Blind street musicians playing the Kobza, a Ukrainian folk music instrument, for our purposes kobzar=lirnyk=banduryst ↩︎

-

“shelves” almost makes me cry, but the third line is perfect, haven’t found any other normal rhyme…. ↩︎

-

For now “city square”; More about the connotations of this word, as I see them, further down ↩︎

-

Formerly “we’ve been together” but this would imply they are /still/ together ↩︎

-

sounds too much like passive and therefore weird, but whatever ↩︎

-

Adding meaning that was not there, but “Maidan” is hard to rhyme with anything. I also can see something like “Where drunken clouds are floating in the trees” ↩︎

-

Four identical rhymes – it’s a feature! increasing the DRAMA and stuff ↩︎