serhii.net

In the middle of the desert you can say anything you want

-

Day 1618 (07 Jun 2023)

GBIF data analysis

Format

- GBIF Infrastructure: Data processing has a detailed description of the flow

occurrences.txtis an improved/cleaned/formalizedverbatim.txt- metadata

meta.xmlhas list of all colum data types etc.- for all files in the zip!

- columns links lead to DCMI: DCMI Metadata Terms

metadata.xmlis things like download doi, license, number of rows, etc.

- .zips are in Darwin format: FAQ

- Because there are cases when both single and double quotes etc., and neither

'/"asquotecharwork.

df = vx.read_csv(DS_LOCATION,convert="verbatim.hdf5",progress=True, sep="\t",quotechar=None,quoting=3,chunk_size=500_000) - Because there are cases when both single and double quotes etc., and neither

Tools

- GBIF .zip parser lib:

- BelgianBiodiversityPlatform/python-dwca-reader: 🐍 A Python package to read Darwin Core Archive (DwC-A) files.

- Tried it, took a long time both for the zip and directory, so I gave up

- gbif/pygbif: GBIF Python client

- API client, can also do graphs etc., neat!

Analysis

Things to try:

limit number of columns throughpd.read_csv.usecols()1 to the ‘interesting’ ones- optionally take a smaller subset of the dataset and drop all

NaNs - take column indexes from

meta.xml - See if someone already did this:BelgianBiodiversityPlatform/python-dwca-reader: 🐍 A Python package to read Darwin Core Archive (DwC-A) files.

- optionally take a smaller subset of the dataset and drop all

- GBIF Infrastructure: Data processing has a detailed description of the flow

-

Day 1617 (06 Jun 2023)

jupyter notebook, lab etc. installing extensions magic, paths etc.

It all started with the menu bar disappearing on qutebrowser but not firefox:

Broke everything when trying to fix it, leading to not working vim bindings in

lab. Now I have vim bindings back and can live without the menu I guess.It took 4h of very frustrating trial and error that I don’t want to document anymore, but - the solution to get vim bindings inside jupyterlab was to use the steps for installing through jupyter of the extension for notebooks, not the recommended lab one.

Installation · lambdalisue/jupyter-vim-binding Wiki:mkdir -p $(jupyter --data-dir)/nbextensions/vim_binding jupyter nbextension install https://raw.githubusercontent.com/lambdalisue/jupyter-vim-binding/master/vim_binding.js --nbextensions=$(jupyter --data-dir)/nbextensions/vim_binding jupyter nbextension enable vim_binding/vim_bindingI GUESS the issue was that previously I didn’t use

--data-dir, and tried to install as-is, which led to permission hell. Me downgrading -lab at some point also helped maybe.The recommended

jupyterlab-vimpackage installed (through pip), was enabled, but didn’t do anything: jwkvam/jupyterlab-vim: Vim notebook cell bindings for JupyterLab.Also, trying to install it in a clean virtualenv and then doing the same with pyenv was not part of the solution and made everything worse.

Useful bits

Getting paths for both

-laband classic:> jupyter-lab paths Application directory: /home/sh/.local/share/jupyter/lab User Settings directory: /home/sh/.jupyter/lab/user-settings Workspaces directory: /home/sh/.jupyter/lab/workspaces > jupyter --paths config: /home/sh/.jupyter /home/sh/.local/etc/jupyter /usr/etc/jupyter /usr/local/etc/jupyter /etc/jupyter data: /home/sh/.local/share/jupyter /usr/local/share/jupyter /usr/share/jupyter runtime: /home/sh/.local/share/jupyter/runtimeRemoving ALL packages I had locally:

pip uninstall --yes jupyter-black jupyter-client jupyter-console jupyter-core jupyter-events jupyter-lsp jupyter-server jupyter-server-terminals jupyterlab-pygments jupyterlab-server jupyterlab-vim jupyterlab-widgets pip uninstall --yes jupyterlab nbconvert nbextension ipywidgets ipykernel nbclient nbclassic ipympl notebookTo delete all extensions:

jupyter lab clean --allRelated: 230606-1428 pip force reinstall package

Versions of everything

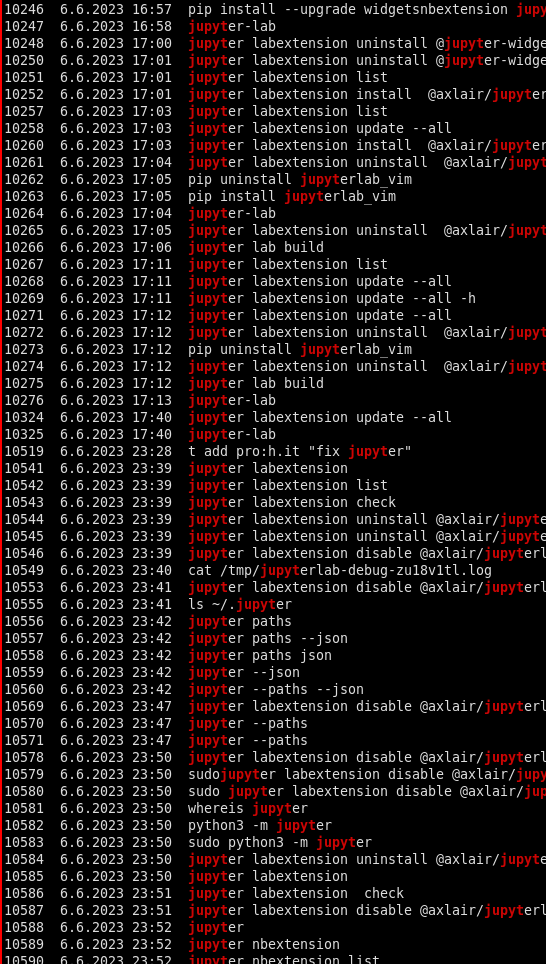

> pip freeze | ag "(jup|nb|ipy)" ipykernel==6.23.1 ipython==8.12.2 ipython-genutils==0.2.0 jupyter-client==8.2.0 jupyter-contrib-core==0.4.2 jupyter-contrib-nbextensions==0.7.0 jupyter-core==5.3.0 jupyter-events==0.6.3 jupyter-highlight-selected-word==0.2.0 jupyter-nbextensions-configurator==0.6.3 jupyter-server==2.6.0 jupyter-server-fileid==0.9.0 jupyter-server-terminals==0.4.4 jupyter-server-ydoc==0.8.0 jupyter-ydoc==0.2.4 jupyterlab==3.6.4 jupyterlab-pygments==0.2.2 jupyterlab-server==2.22.1 jupyterlab-vim==0.16.0 nbclassic==1.0.0 nbclient==0.8.0 nbconvert==7.4.0 nbformat==5.9.0 scipy==1.9.3 widgetsnbextension==4.0.7Bad vibes screenshot of a tiny part of

history | grep jup

“One of the 2.5 hours I’ll never get back”, Serhii H. (2023).

Oil on canvas

Kitty terminal,scrotscreenshotting tool, bash.

Docker unbuffered python output to read logs live

Docker image runs a Python script that uses

print()a lot, butdocker logsis silent because pythonprint()uses buffered output, and it takes minutes to show.Solution1: tell python not to do that through an environment variable.

docker run --name=myapp -e PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1 -d myappimage

pip force reinstall

TIL about

pip install packagename --force-reinstall1

-

Day 1616 (05 Jun 2023)

Useful writing cliches

- Since then, we have witnessed an increased research interest into

- Technical developments have gradually found their way into

- comprehensive but not exhaustive review

…

(On a third thought, I realized how good ChatGPT is at suggesting this stuff, making this list basically useless. Good news though.)

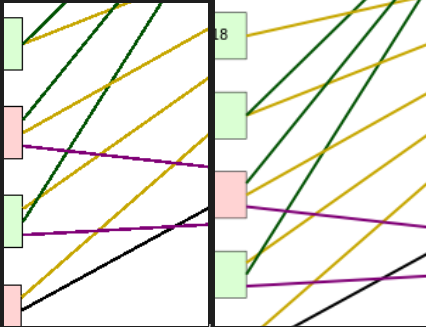

Dia save antialiased PNG

I love Dia, and today I discovered that:

- It can do layers! That work as well as expected in this context

- To save an antialiased PNG, you have to explicitly pick “png (antialiased)” when exporting, it’s in the middle of the list and far away from all the other flavours of .png extensions

Before and after:

-

Day 1615 (04 Jun 2023)

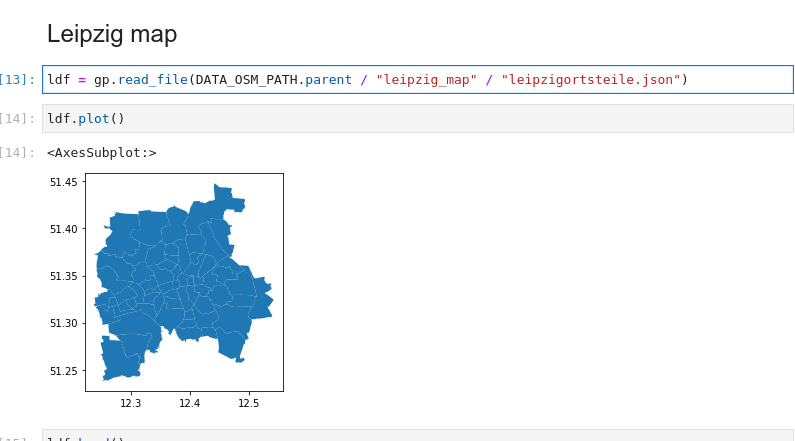

Adventures in plotting things on maps

So I have recorded a lot of random tracks of my location through the OSMAnd Android app and I wanted to see if I can visualize them. This was a deep dive into the whole topic of visualizing geo data.

Likely I got some things wrong but I think I have a picture more or less of what exists, and I tried to use a lot of it.

Basics

Formats

GPX

OSMAnd gives me

.gpxfiles.(I specifically would like to mention OsmAnd GPX | OsmAnd, that I should have opened MUCH earlier, and that would have saved me one hour trying to understand why do the speeds look strange: they were in meters per second.)

A GPX file give you a set(?) of tracks composed of segments that are a list of points, with some additional optional attributes/data with them.

GeoJSON

Saw it mentioned the most often, therefore in my head it’s an important format.

Among other things, it’s one of the formats Stadt Leipzig provides data about the different parts of the city in, and I used that data heavily: Geodaten der Leipziger Ortsteile und Stadtbezirke - Geodaten der Leipziger Ortsteile - Open Data-Portal der Stadt Leipzig

Less important formats

Are out of scope of this and I never used them, but if I had to look somewhere for a list it’d be here: Input/output — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation

Getting data

- Export | OpenStreetMap is awesome, and I used it really often to get GPS coordinates of places when I needed it.

- Random gov’t websites provide geospatial data surprisingly often! Including the already mentioned city of Leipzig.

- Some maps can be downloaded automagically from python code just by providing not even coordinates, but a plain text location like an address! Below there will be examples but Guide to the Place API — contextily 1.1.0 documentation made me go “wow that’s so cool!” immediately

- A lot of apps can record GPX tracks, it seems to be the de-facto standard format for that (be it for hiking / paragliding / whatever)

Libraries

gpgpy for reading GPX files

Really lightweight and is basically an interface to the XML content of such files.

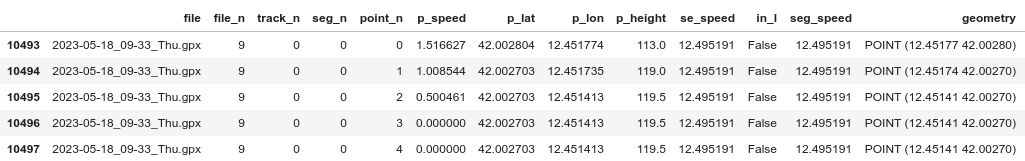

import gpxpy # Assume gpx_tracks is a list of Paths to .gpx files data = list() for f in tqdm.tqdm(gpx_tracks): gpx_data = gpxpy.parse(f.read_text()) # For each track inside that file for t in gpx_data.tracks: # For each segment of that track for s in t.segments: # We create a row el = {"file": f.name, "segment": s} data.append(el) # Vanilla pd.DataFrame with those data df = pd.DataFrame(data) # We add more info about each segment df["time_start"] = df["track"].map(lambda x: x.get_time_bounds().start_time) df["time_end"] = df["track"].map(lambda x: x.get_time_bounds().end_time) df["duration"] = df["track"].map(lambda x: x.get_duration()) dfAt the end of my notebook, I used a more complex function to do the same basically:

WITH_OBJ = False LIM=30 data = list() # Ugly way to enumerate files fn = -1 for f in tqdm.tqdm(gpx_tracks[:LIM]): fn += 1 gpx_data = gpxpy.parse(f.read_text()) for tn, t in enumerate(gpx_data.tracks): for sn, s in enumerate(t.segments): # Same as above, but with one row per point now: for pn, p in enumerate(s.points): # We get the speed at each point point_speed = s.get_speed(pn) if point_speed: # Multiply to get m/s -> km/h point_speed *= 3.6 el = { "file": f.name, "file_n": fn, "track_n": tn, "seg_n": sn, "point_n": pn, "p_speed": point_speed, "p_lat": p.latitude, "p_lon": p.longitude, "p_height": p.elevation, } # If needed, add the individual objects too if WITH_OBJ: el.update( { "track": t, "segm": s, "point": p, } ) data.append(el) ft = pd.DataFrame(data) gft = gp.GeoDataFrame(ft, geometry=gp.points_from_xy(ft.p_lon, ft.p_lat))Then you can do groupbys etc by file/track/segment/… and do things like mean segment speed:

gft.groupby(["file_n", "track_n", "seg_n"]).p_speed.transform("mean") gft["seg_speed"] = gft.groupby(["file_n", "track_n", "seg_n"]).p_speed.transform("mean")

GeoPandas

GeoPandas 0.13.0 — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation

It’s a superset of pandas but with more cool additional functionality built on top. Didn’t find it intuitive at all, but again new topic to me and all that.

Here’s an example of creating a

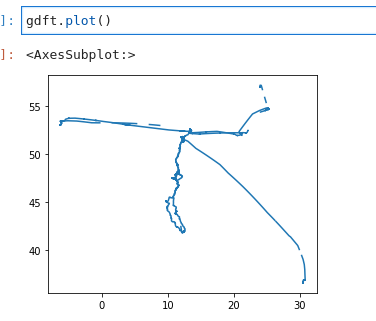

GeoDataFrame:import geopandas as gp # Assume df_points.lon is a pd.Series/list-like of longitudes etc. pdf = gp.GeoDataFrame( df_points, geometry=gp.points_from_xy(df_points.lon, df_points.lat) ) # we have a GeoDataFrame that's valid, because we created a `geometry` that gets semantically parsed as geo-data now!Theoretically you can also read .gpx files directly, adapted from GPS track (GPX-Datei) in Geopandas öffnen | Florian Neukirchen to use

pd.concat:gdft = gp.GeoDataFrame(columns=["name", "geometry"], geometry="geometry") for file in gpx_tracks: try: f_gdf = gp.read_file(file, layer="tracks") gdft = pd.concat([gdft, f_gdf"name", "geometry"]) except Exception as e: pass # print("Error", file, e)Problem with that is that I got a GeoDataFrame with shapely.MultiLineStrings that I could plot, but not easily do more interesting stuff with it directly:

Under the hood, GeoPandas uses Shapely a lot. I love shapely, but I gave up on directly reading GPX files with geopandas", and went with the gpgpy way described above.

Spatial Joins

Merging data — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation, first found on python - Accelerating GeoPandas for selecting points inside polygon - Geographic Information Systems Stack Exchange

Are really cool, and you can merge two different geodataframes based on whether things are inside/intersecting/outside other things, with the vanilla join analogy holding well otherwise.

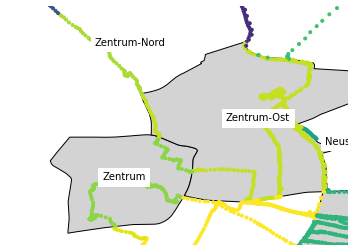

FOR EXAMPLE, we have the data about Leipzig

ldffrom before:

We can

pdf = pdf.sjoin(ldf, how="left", predicate="intersects")it with our

pdfdataframe with points, it automatically takes thegeometryfrom both, finds the points that are inside different parts of Leipzig, and you get your points with the columns from the part of Leipzig they’re located at!Then you can do pretty graphs with the points colored based on that, etc.:

TODO

Adding a background map to plots — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation contextily/intro_guide.ipynb at main · geopandas/contextily · GitHub DenisCarriere/geocoder: Python Geocoder API Overview — geocoder 1.38.1 documentation Sampling Points — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation

Guide to the Place API — contextily 1.1.0 documentation Quickstart — Folium 0.14.0 documentation A short look into providers objects — contextily 1.1.0 documentation plugins — Folium 0.14.0 documentation masajid390/BeautifyMarker Plotting with Folium — GeoPandas 0.13.0+0.gaa5abc3.dirty documentation

- Folium exporting map as html through

html_code = m.get_root()._repr_html_()

-

Day 1610 (30 May 2023)

Radar plots

The Radar chart and its caveats: “radar or spider or web chart” (c)

… are best done in plotly:

For a log axis:

fig.update_layout( template=None, polar = dict( radialaxis = dict(type="log"), )EDIT: for removing excessive margins, use

fig.update_layout( margin=dict(l=20, r=20, t=20, b=20), )

-

Day 1609 (29 May 2023)

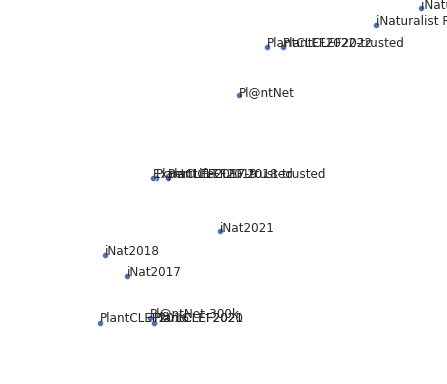

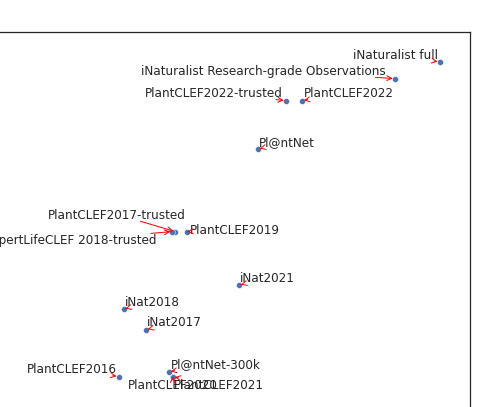

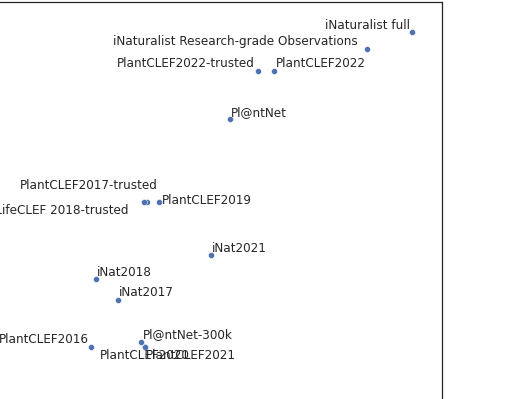

Seaborn matplotlib labeling data points

Trivial option: Label data points with Seaborn & Matplotlib | EasyTweaks.com

TL;DR

for i, label in enumerate (data_labels): ax.annotate(label, (x_position, y_position))BUT! Overlapping texts are sad:

SO sent me to the library Home · Phlya/adjustText Wiki and it’s awesome

fig, ax = plt.subplots() plt.plot(x, y, 'bo') texts = [plt.text(x[i], y[i], 'Text%s' %i, ha='center', va='center') for i in range(len(x))] # adjust_text(texts) adjust_text(texts, arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='red'))Not perfect but MUCH cleaner:

More advanced tutorial: adjustText/Examples.ipynb at master · Phlya/adjustText · GitHub

Pypy doesn’t have the latest version, which has:

min_arrow_len- some other bits like

expand - more: adjustText/init.py at master · Phlya/adjustText · GitHub

Plant datasets taxonomy prep

This contains the entire list of all datasets I care about RE [230529-1413 Plants datasets taxonomy] for 230507-2308 230507-1623 Plants paper notes

-

GBIF

- Search

- Seems to be a central place for all similar and not-similar datasets with a centralized API

-

Pl@ntNet

- FULL dataset: Pl@ntNet observations

-

- https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?dataset_key=7a3679ef-5582-4aaa-81f0-8c2545cafc81

- Contains num of species and yet another exploring thing:World flora: Species - Pl@ntNet identify

-

- datamanager @ data

- Not sure what this is but sounds interesting, maybe connected to downloading their stuff

-

- OpenReview review of their paper: Pl@ntNet-300K: a plant image dataset with high label ambiguity and a long-tailed distribution | OpenReview

- FULL dataset: Pl@ntNet observations

-

- portuguese-only?

-

Flora-On: Flora de Portugal Interactiva. (2023). Sociedade Portuguesa de Botânica. www.flora-on.pt. Consulta efectuada em 29-5-2023.

- Used in <

@herediaLargeScalePlantClassification2017(2017) z/d>

-

iNaturalist-xxx

- Has 2017-2018-… variants

- train/val plants numbers in the paper, test sets unclear and needs to be downloaded to calculate

- consensus (kaggle, paperswithcode etc.) seems to be train/val use for all of them

- Competitions

- All: visipedia/inat_comp: iNaturalist competition details

- 2017:

- (seems to be the coolest/most_used dataset)

- Plantae, Insecta,Aves,Reptilia,Mammalia,Fungi,Amphibia,Mollusca,Animalia,Arachnida,Actinopterygii,Chromista

- rows: supercategory (animalia, etc.), per-image attribution and license, GBIF (id, link, ..), others

- Sample rows from dataset: iNat competition GBIF info - Google Sheets

- <

@vanhornINaturalistSpeciesClassification2018(2018) z/d>

- Added the rest to the spreadsheet, 2019 is the only one with missing per-category things

-

INaturalist

- Website is mirrored in GBIF

- You can filter stuff in the website and get numbers, GBIF has a viewer that also can do things but not list of species

- ‘research grade’ are the good observations: Help · iNaturalist

- SPECIES!=IDENTIFIER! The latter seems to contain also families etc.

- “iNaturalist Research-grade Observations”

- On GBIF is the entire dataset: Occurrence search

- This is the filter they used on iNaturalist: Observations · iNaturalist

- Plants-only GBIF: Occurrence search

- GBIF file with ‘species lst’: Download

- It contains 129k records, but they aren’t just species, also families etc.

- Corresponding iNat filter: Observations · iNaturalist

- GBIF file with ‘species lst’: Download

- On GBIF is the entire dataset: Occurrence search

- Plant seedlings dataset

- https://github.com/TheSaintIndiano/Plant-Seedlings-Classification/blob/master/Seedlings.ipynb

- num of images based on that doc: 390+ 611+ 231+ 496+ 221+ 475+ 287+ 385+ 221+ 654+ 516+ 263

-

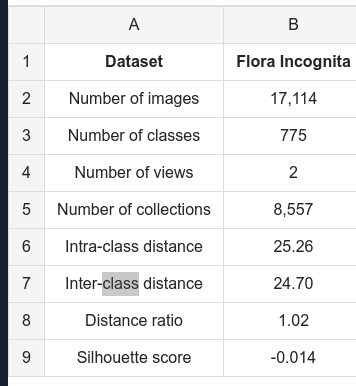

Flora Incognita

- A lot of conflicting info!

- Main site: Flora Incognita | EN – The Flora Incognita app – Interactive plant species identification

- 16k+ plant types

- Main site: Flora Incognita | EN – The Flora Incognita app – Interactive plant species identification

- 2020 Paper giving some numbers about the dataset Multi-view classification with convolutional neural networks | PLOS ONE

-

- 775 classes

-

- 2021 paper about app with some details about the num of plants and comparison to other datasets: The Flora Incognita app – Interactive plant species identification - Mäder - 2021 - Methods in Ecology and Evolution - Wiley Online Library

- 4851 classes in table 1

- Flora Capture: a citizen science application for collecting structured plant observations - PMC

- Flowers, leaves or both? How to obtain suitable images for automated plant identification - PubMed is about the number of images for classification, and

we curated a partly crowd-sourced image dataset, comprising 50,500 images of 101 species.

- Paper using FI app, not FI dataset itself! Plant image identification application demonstrates high accuracy in Northern Europe | AoB PLANTS | Oxford Academic

2494 observations with 3199 images from 588 species, 365 genera and 89 families

- A lot of conflicting info!

-

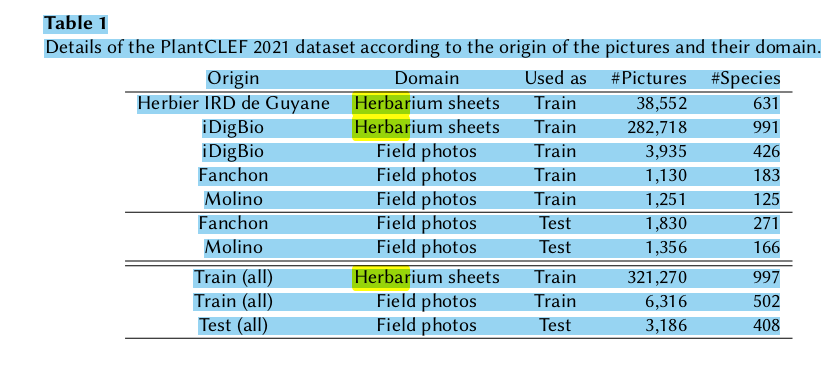

PlantCLEF

- PlantCLEF2021

- PlantCLEF 2021 | ImageCLEF / LifeCLEF - Multimedia Retrieval in CLEF

-

- TRAIN: 321270 herb sheets, 6316 field photos, 354 observations of both herbarium+field; TEST SET: “3,186 photos in the field related to 638 plant observations (about 5 pictures per plants on average).”

- Dataset here: https://zenodo.org/record/3658343#.ZDe9x1qxVhE

- PlantCLEF2021

REALLY NICE OVERVIEW PAPER with really good overview of the existing datasets! Frontiers | Plant recognition by AI: Deep neural nets, transformers, and kNN in deep embeddings

-

Flavia

-

Datasets | The Leaf Genie has list of leaf datasets! TODO

-

Herbarium 2021

- Huge ds and paper linking to smaller ones - preliminarily added them to the spreadsheet

- [[2105.13808] The Herbarium 2021 Half-Earth Challenge Dataset](https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.13808

- <

@delutioHerbarium2021HalfEarth2021(2021) z/d>)

Next steps

Spreadsheet

- Update it for all the sub-datasets if practical - e.g. web and friends if needed

- Done

Datasets

- Nice picture of who stole from whom

- Done